Page 518 - The Secret Museum

P. 518

ON THE DAY I VISITED, the club had just hosted the Olympics and was filled with

workmen taking down the London 2012 multi-coloured signs and reinstating the

traditional purple and green colours of Wimbledon. The museum itself was closed,

but Honor Godfrey, curator of the museum took me behind the scenes. In the club’s

museum stores are about 450 plans drawn up by architect Stanley Peach, who

designed Centre Court, which opened in 1922.

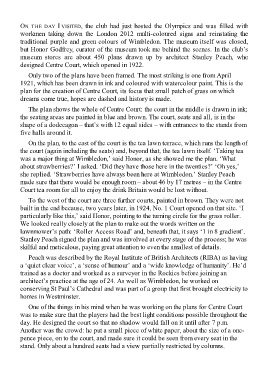

Only two of the plans have been framed. The most striking is one from April

1921, which has been drawn in ink and coloured with watercolour paint. This is the

plan for the creation of Centre Court, its focus that small patch of grass on which

dreams come true, hopes are dashed and history is made.

The plan shows the whole of Centre Court: the court in the middle is drawn in ink;

the seating areas are painted in blue and brown. The court, seats and all, is in the

shape of a dodecagon – that’s with 12 equal sides – with entrances to the stands from

five halls around it.

On the plan, to the east of the court is the tea lawn terrace, which runs the length of

the court (again including the seats) and, beyond that, the tea lawn itself. ‘Taking tea

was a major thing at Wimbledon,’ said Honor, as she showed me the plan. ‘What

about strawberries?’ I asked. ‘Did they have those here in the twenties?’ ‘Oh yes,’

she replied. ‘Strawberries have always been here at Wimbledon.’ Stanley Peach

made sure that there would be enough room – about 46 by 17 metres – in the Centre

Court tea room for all to enjoy the drink Britain would be lost without.

To the west of the court are three further courts, painted in brown. They were not

built in the end because, two years later, in 1924, No. 1 Court opened on that site. ‘I

particularly like this,’ said Honor, pointing to the turning circle for the grass roller.

We looked really closely at the plan to make out the words written on the

lawnmower’s path: ‘Roller Access Road’ and, beneath that, it says ‘1 in 8 gradient’.

Stanley Peach signed the plan and was involved at every stage of the process; he was

skilful and meticulous, paying great attention to even the smallest of details.

Peach was described by the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) as having

a ‘quiet clear voice’, a ‘sense of humour’ and a ‘wide knowledge of humanity’. He’d

trained as a doctor and worked as a surveyor in the Rockies before joining an

architect’s practice at the age of 24. As well as Wimbledon, he worked on

conserving St Paul’s Cathedral and was part of a group that first brought electricity to

homes in Westminster.

One of the things in his mind when he was working on the plans for Centre Court

was to make sure that the players had the best light conditions possible throughout the

day. He designed the court so that no shadow would fall on it until after 7 p.m.

Another was the crowd: he put a small piece of white paper, about the size of a one-

pence piece, on to the court, and made sure it could be seen from every seat in the

stand. Only about a hundred seats had a view partially restricted by columns.